Directed by Craig McCall

***

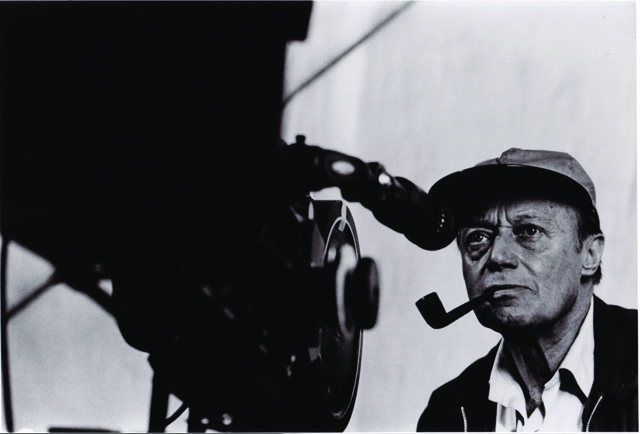

British cinematographer Jack Cardiff is a poster child for career longevity. Entering the film business as a 4-year-old actor in 1918, Cardiff had moved behind-the-camera by his late teens and continued to work right up until his death in 2009 at the age of 94. Along the way, he photographed almost 70 features—from landmark classics like The Red Shoes to meat-and-potatoes efforts like Rambo: First Blood Part II—and directed a handful of films as well, including the award-winning Sons and Lovers. He was also a front-line observer to the radical changes in the film industry that occurred over that multi-decade period, from the rise and fall of the studio system from the ‘30s to the ‘60s, to the temporary collapse of Britain’s film industry in the ‘70s and the infusion of international money into the marketplace in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Sadly, Craig McCall’s affectionate tribute to Cardiff’s epic career doesn’t make more of the changing times he lived through. Instead Cameraman is primarily an extended clip reel that showcases select scenes from his subject’s work, punctuated by interviews with Cardiff as well as his many contemporaries and admirers. Fortunately, the clips are grand enough—and Cardiff is engaging and insightful enough—to make the film a modest pleasure. By far, the most interesting section is devoted to the cinematographer’s working relationship with Michael Powell and Emerich Pressburger, with whom he collaborated on three memorable films, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus and the aforementioned Red Shoes. (If Cameraman accomplishes nothing else, it should encourage audiences to run out and watch those pictures—along with the rest of Powell & Pressburger’s marvelous filmography—again or for the first time.) Cardiff also has some hilarious memories to share about his time making The African Queen for John Huston. The rest of his extensive filmography passes by in something of a haze, as McCall jumps from clip to clip, only occasionally pausing to offer more context about the film in question. For example, the fantastical 1951 romance Pandora and the Flying Dutchman is discussed somewhat at length, but other films are granted only cursory explanations. And even though the film is subtitled The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff, the subject of Cardiff’s personal life is rarely touched on—we’re never even told whether he married or had children. (Not that McCall needed to turn this into some kind of an E! True Hollywood Story, but it would have been interesting to know whether his career kept him from having a family and if that weighed on him at all.) Still, while Cameraman isn’t as thorough as it could and perhaps should be, it does give moviegoers a deeper appreciation for the art and craft of cinematography in general and Cardiff’s work in particular.