Posted by Ethan under Film Festivals, Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on NYFF ’10: Boxing Gym

Boxing Gym

Directed by Frederick Wiseman

***1/2

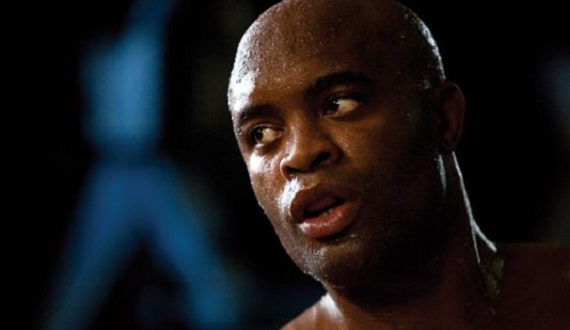

In a year dominated by documentaries that play more like fiction—think Catfish and I’m Still Here—thank goodness we still have Frederick Wiseman around to show us how old-school cinema verite is done. A titan in the documentary world (in influence if not necessarily box office), Wiseman has been making observational portraits of American life and institutions since the late 1960s, with movies like High School, Public Housing and Domestic Violence. His latest, Boxing Gym, is one of his less weighty films—at least when compared to something like Domestic Violence and its sequel—but it’s still a terrific example of his aesthetic. For several months, Wiseman and his camera crew set up shop at an Austin, Texas-based boxing gym and documented the facility’s daily workings, filming sparring sessions, individual workouts, off-the-cuff, shoot-the-shit kind-of conversations and even registration sessions where the gym’s owner and chief trainer signs up new members. As is typical in a Wiseman film, there’s no narration, no lower-third ID’s telling us a person’s name, no outside information beyond what we see on the screen. The style is so different from contemporary documentaries—to say nothing of reality television—it can be difficult to adjust to at first. But as the film goes on, you find yourself falling into the rhythm of this gym, recognizing faces and growing familiar with the surroundings. It helps that the gym itself is such a visually interesting place. This ain’t a ritzy Crunch or New York Sports Club facility, it’s a small, grungy, lived-in space with memorabilia lining the walls and well-used equipment covering every bare bit of floor. In other words, it’s a serious place and the cliental take their workouts seriously, but never to the point where they can’t share a laugh with or lend a hand to a fellow gym-goer. As excited as I am by the new narrative and formal possibilities that contemporary documentaries are experimenting with, it’s a shame that fewer directors are making beautifully observed slice-of-life movies like Boxing Gym.

Boxing Gym opens at the IFC Center in New York on October 22.