Fri 1 Oct 2010

NYFF ’10: Carlos

Posted by Ethan under Film Festivals, Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on NYFF ’10: Carlos

Directed by Olivier Assayas

***1/2

Since its premiere at Cannes last summer, Olivier Assayas’ five-and-a-half hour chronicle of the career of Carlos the Jackal has frequently been compared to Steven Soderbergh’s Che, another lengthy, multi-part film about an iconic political figure who, depending on who you ask, is either a terrorist or a freedom fighter.

While the two movies do have a number of things in common, I find Che to be a far more radical film in terms of its execution, specifically Soderbergh’s decision to essentially eliminate any mention of Che Guevera’s private life. In both halves of Che, the movie’s subject is never granted any quiet moments away from the revolution to express his thoughts and feelings about other things—live, love and the like. Not everyone was pleased with Soderbergh’s approach, but it happened to be one of my favorite things about his film. After all, those are precisely the kind of scenes that often get biopics into trouble, as writers and directors feel compelled to overdramatize personal matters like addiction and marital strain (see Ray, Walk the Line and virtually any biopic about out-of-control musicians) or reduce pivotal moments in the subject’s life—say the death of a loved one or the birth of an idea—to a few lines of dialogue or a single, silly “Eureka!†moment.

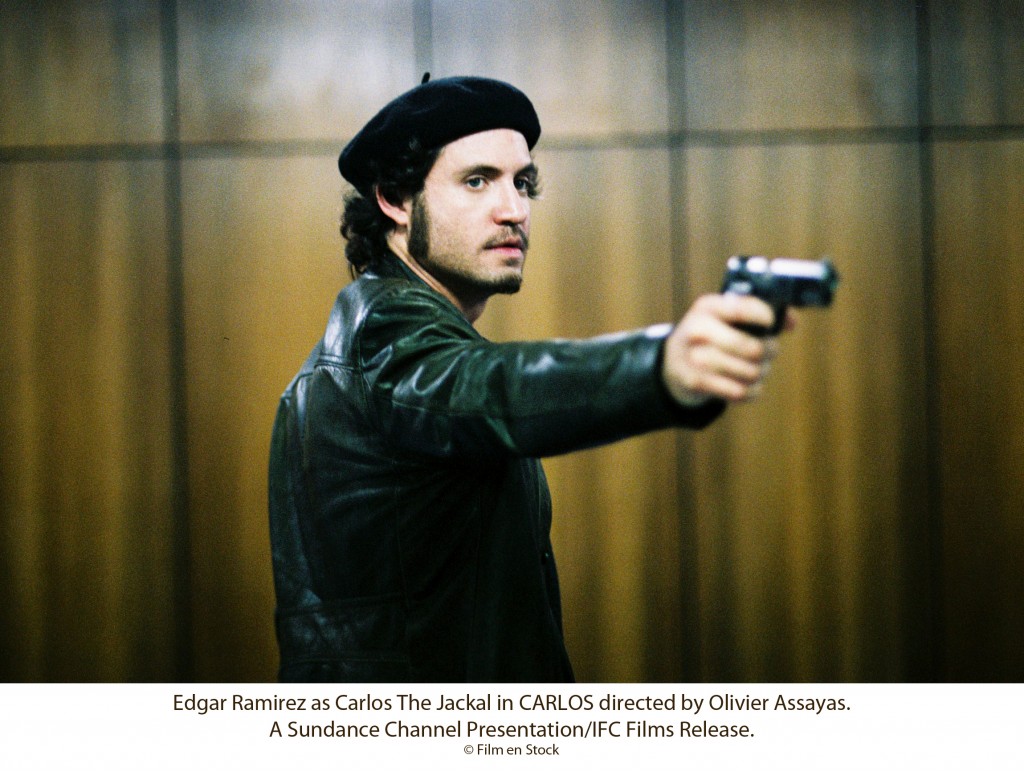

It’s no coincidence that those kinds of scenes are also the weakest parts of Carlos; early on, for example, there’s a strained sequence where Ilich Ramirez Sanchez a.k.a. Carlos (played by Edgar Ramirez) debates his goals with his lover and fellow revolutionary, which is followed by an equally on-the-nose bit where he officially adopts his world-famous moniker. Fortunately, there are relatively few of these scenes in the movie’s 319-minute runtime. Instead, much like Soderbergh, Assayas is primarily interested in the process by which Carlos organizes and executes his various missions. If Che offers a remarkably detailed presentation of guerilla warfare, Carlos provides an equally comprehensive depiction of urban terrorism. The highlight of the film is Carlos’ famous 1975 OPEC raid, when he took hostage some sixty dignitaries and their assistants. Lasting almost 90 minutes, this set-piece is a brauva bit of filmmaking that ranks up there with the best action sequences of the past few years.

The OPEC raid also functions as a natural narrative midpoint for the film, showing us just how far Carlos has come while also laying the seeds for his eventual destruction. Where Che remained largely unchanged in both parts of Soderbergh’s movie—his circumstances in Cuba and Bolivia were different, but his ideals and fighting spirit never dimmed—Assayas shows just how much Carlos changed over the course of his career. The first half of the film presents him as a dashing, daring revolutionary firmly committed to the revolution. But in the aftermath of the OPEC raid—which ended with him accepting a $20 million ransom instead of following his orders to kill the hostages if his original terms were not met—Carlos’ ideals ran up against the desire to profit from his ventures. Slowly, but surely he became a terrorist-for-hire, marketing his skills to various governments, all of whom would later turn their backs on him when he became a liability. By the end of the film, he’s an overweight, drunken has-been who spends much of his time chasing after women in bars. Ramirez’s physical transformation over the course of the movie’s decade-spanning narrative is nothing short of astonishing; it’s almost hard to believe the same actor is portraying the older, not-so-wiser Carlos. In the end, Che is the story of one man’s revolution, while Carlos is the story of one man’s life.

Carlos opens in New York on October 15 in both the 319-minute version and a 165-minute version. In addition, it will air in three parts on the Sundance Channel starting October 11.

No Responses to “ NYFF ’10: Carlos ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.