Tue 22 Feb 2011

Dancing with the Devil

Posted by Ethan under Features, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Dancing with the Devil

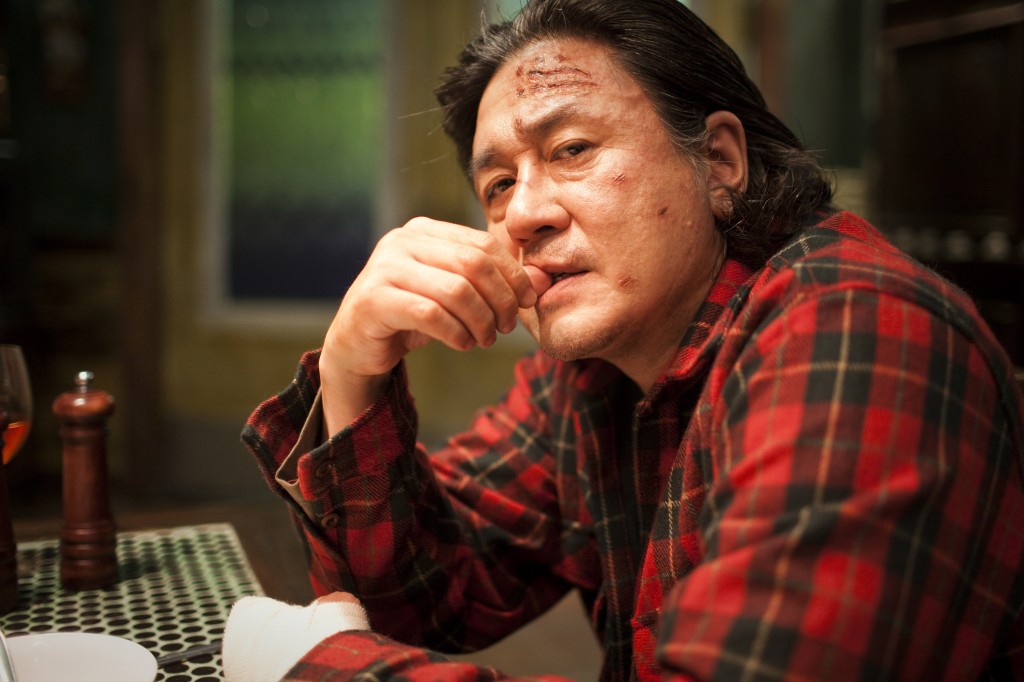

Korean director Kim Jee-woon brings his unique brand of genre filmmaking to the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s BAMcinematek program with the six-film retrospective Severely Damaged, which kicks off this Friday the 25th with the New York premiere of his latest film, I Saw the Devil. The series runs until March 2 and includes Kim’s debut feature The Quiet Family, his recent western The Good, The Bad and The Weird and, my personal favorite, the 2003 horror film A Tale of Two Sisters. (You can read my reviews of both the original film and its 2009 Hollywood remake here and here.) I interviewed the director–who will be present for a Q&A following the Devil screening–via email for a story that’s appearing in this week’s issue of the The Brooklyn Paper. Because I had to leave some of his comments on the cutting room floor due to space, I’m running the full text of the interview below. I’ll have my thoughts about I Saw the Devil posted sometime next week, before its theatrical release on March 4th.

Q: You’ve tackled a wide variety of genres over the course of your career. Do you go into a film with the genre in mind first and then craft a story to fit the genre?

Kim Jee-woon: When I decide on a new project, I usually reflect on some emotion or feeling from my previous project. For example, my debut The Quiet Family was a genre-combination that mixed comedy and horror. As some may know, that film is closer to a sitcom than a straight narrative. After that, I wanted to do something that had more of a dramatic element with a stronger narrative flow, and so I made The Foul King. And after that I wanted to do a woman’s story so I made the short film Memories and then A Tale of Two Sisters. Wondering what a male version of Sisters might be like, I looked to combine the delicate feminine qualities of that film with a forceful male element by making A Bittersweet Life. Because that film was an inward look into the uncertainties of one man, I wanted to make a more outgoing film next, which was The Good, The Bad and The Weird. And that was such a large-scale, spectacle-centric film that I wanted to do something more tightly planned next and the result is I Saw the Devil.

Working like this, I first draw up the mood or sense of my next film and then decide on a genre. Because what’s most important is picking the right genre that will best express that idea in my head. I’d like to think that my next film will be something at a different point than what I’m making now. Quenching the thirst, so to speak, of what is lacking now.

Q: Many American films that deal with vengeance generally conclude with the hero walking away mostly at peace, knowing that justice has been served. The finale here is far less tidy—it’s clear that the wronged man has gotten little, if any, satisfaction from his actions. That idea plays out in Park Chan-wook’s Vengenace trilogy as well. Does that reflect a larger attitude in Korean culture—the notion that revenge doesn’t lead to emotional reward?

KJW: Well, I’d have to say this is personally my own way of dealing with films concerned with vengeance. All these revenge films end the same way—they have these sudden closures with a forced ethical resolution or false happy endings. I made this film feeling frustrated and dissatisfied with those movies and thinking of a new form of revenge film.

Also, rather than chasing the target for revenge for two hours and getting that revenge anticlimactically at the end, I wanted to put a new kind of tension by having the two meet suddenly in the midpoint of the film. I thought that puts the audience a step closer to the realistic emotions of revenge. Because it starts from the point of imagining the victim’s fear and pain, reliving one’s own emotional and mental suffering and then wanting to exact the very same degree of hurt. In order to do that, he must carry out the same deeds that this devil has done by becoming a devil himself. And there is the internal dilemma, this unavoidable situation where he must become a devil to punish the devil. This man’s tragic and desperate vengeance provides the film’s theme and frame. Exacting revenge means placing the target of your revenge at a point of no return and a successful vengeance simultaneously means that you must accept your what you’ve lost and the sorrowful pain of that.  I wanted to depict those kinds of emotions.

Q: Your films pay close attention to their environments—that house in A Tale of Two Sisters and the wide-open landscapes in The Good, The Bad and the Weird. Is location scouting and production design a particularly enjoyable part of the filmmaking process for you?

KJW: I think that a film has to be able to tell a story with all the elements contained in the frame. Not just what you see but even what you hear. Things like locations and even sound are not secondary parts—you have to see them as equals to the actors’ performances. The films that awe and surprise me are the ones that really converse with their audience and present an enjoyable experience this way.

So to answer the question, more than a particularly enjoyable process for myself, I see it as one of the most basic manners for making a film. The theme of A Tale of Two Sisters was the painful recollection of a buried memory provoked by a certain place and object, so the two things naturally had to be searingly lucid. The crazy chase in the vast open spaces of The Good, The Bad and the Weird was the reflection of a certain lifestyle and so that had to be emphasized there. That’s why in my films the wallpaper speaks and the wide-open plains strike up a conversation with you.

Q: The film depicts its extreme violence in a surprisingly casual manner, which makes it more horrific, but also less shocking in a strange way. How do you maintain that casual nature on set, given that special effects are often involved in crafting those scenes? Do you rigorously storyboard and plan those scenes in advance or do you try for a more spontaneous style on set?

KJW: If something is horrific to watch in I Saw the Devil, it’s probably because the film portrays the emotions of revenge more directly and more realistically than the depictions we’ve become accustomed to seeing in movies. The actions of vengeance themselves are horrific to see, but no matter how repulsive, it’s still possible for us to filter them with our minds because it’s happening in a movie. The violent scenes may be horrendous and overpowering for those who aren’t used to these films, but for those who can’t get enough of these it may be nothing out of the ordinary. I think the cruel emotions of the characters in this film appeals to the audience in a very straightforward, strong and insistent way. It puts audiences in the uncomfortable position of having to understand the characters’ dire situation and emotions, despite knowing they are morally or ethically unacceptable.

We do storyboard those scenes. They function like a highway for the shoot on set—things go well on the route since we plan, share and agree. But because a shoot is like a living thing, some factor or situation might arise or something more forceful that what we had planned and agreed upon might burst onto the road. I think there’s something very important on set, that you don’t know until you’re there. Much is planned and I follow that on set but I also tend to readily accept an idea that pops up in mind in the process. A lot more things come to me when I’m on set and they strongly inspire and grip me.

Q: What lessons—technical or narrative—have you learned from your past films that you applied to I Saw the Devil?

KJW: When planning a film, I first think of the space. After I’m able to shape up how that space feels and how it can work in the film, then I start making characters. Working like this I tend to cling to the space too much—when I make a space or find one from location scouting, I use all the nooks and crannies of that space and make a story and often found myself losing the flow or rhythm. For this film I tried to express the spaces as best I could without putting pressure on the sense of time, which was my top priority.

I think the flow has improved from my previous films. The unnecessary time spent on shoots has decreased significantly. And whereas I used to prefer very strong contrasts and distinct saturations of color, I let go of those attachments and made the color and light contrasts that the specific scenes demanded. By doing so, the film became more realistic looking and, since it fits a certain genre, a lot more creepy.

Q: Most of the Korean films that tend to get U.S. distribution are action or horror movies. From your perspective, are those the easiest genres to cross borders? Could a Korean comedy or melodrama break out here in the same way?

KJW: Genre films are made to fit in that genre’s preconceived style or structural codes that are somewhat common across the world and they naturally make a good subject for a community of consumers to gather around them. I suppose horror or action films have some of the strongest genre codes and sense of style, so they have the advantage of communicating easily over cultural or other barriers. Melodrama is shaped very much by a nation or region’s cultural sensibilities and social traditions that I think besides sharing larger themes, getting satisfaction in the details will be less impactful. Comedy also has to be able to exude that society’s air and reflect its circumstances, so I think those are less friendly across cultures.

Q: Did you ever see the American remake of A Tale of Two Sisters to see how your work was interpreted? Could you ever imagine anyone remaking of I Saw the Devil?

KJW: I’ll leave it at ‘no comment’ on the remake of A Tale of Two Sisters.

As for I Saw the Devil, I thought about doing a remake of it myself by reworking an adaptation from the middle of the story when the killer is first served his revenge and plans a counterattack. It would likely be a very different kind of movie from the Korean version. I think it would be a thriller with a very strong element of entertainment.

Q: What’s your next film? Which genre will it tackle?

KJW: There isn’t anything concrete yet. I suppose it would be something that can quench what thirst I might have felt while making I Saw the Devil.

No Responses to “ Dancing with the Devil ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.