Sat 6 Nov 2010

A Farewell to An Arm

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on A Farewell to An Arm

127 Hours

Directed by Danny Boyle

Screenplay by Danny Boyle and Simon Beaufoy

Starring James Franco, Amber Tamblyn and Kate Mara

****

Regardless of how the rest of the film turns out, Danny Boyle can always be counted on to deliver a killer opening sequence.

Think back to those first few moments of Trainspotting, where Ewan McGregor races headlong through the streets of Edinburgh to the pounding beat of Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life.â€Â Or how about that terrific set-piece that kicks of 28 Days Later, where Cillian Murphy wanders through a deserted London wondering whether he’s the last man in the world. Even lesser entries in Boyle’s canon like A Life Less Ordinary, The Beach and (for me, at least) Slumdog Millionaire open with scenes that bristle with the director’s energy and wit.  That makes it all the more disappointing when the rest of the movie is unable to live up to the promise of those early moments, most often because Boyle loses his focus. His best films—which I consider to be Trainspotting, 28 Days Later and roughly two-thirds of Sunshine—are all, at heart, small-scale survival stories about one character’s attempts to live through difficult circumstances, be it heroin addiction, a zombie-infested city or a doomed spacecraft headed directly towards the sun.

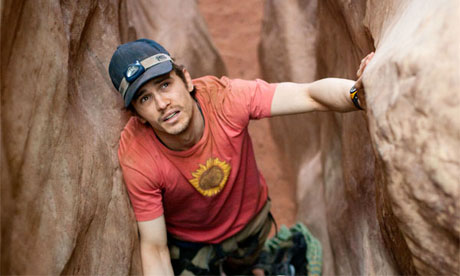

127 Hours is Boyle’s most contained film yet, unfolding largely in a single location with a single actor over a brief five-day span. Not coincidentally, it’s also his best picture since 28 Days Later and a vast improvement over the Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire, where he never overcame the unwieldy back-and-forth narrative structure or the lack of a strong central performer. And, yes, 127 Hours—which is based on a true story—does sport a terrific opening sequence, one that puts you right inside the head of its main character and gets you pumped for the movie ahead. While the infectious Free Blood techno tune “Never Here Surf Music Again†blasts on the soundtrack, we watch the early morning routine of outdoor enthusiast Aron Ralston (played by James Franco) as he prepares to make the trek to Utah’s Canyonlands National Park for a full day of hiking, biking and canyoneering. Making excellent use of split-screen, Boyle shows Ralston assembling his gear and setting off on his journey alongside images of cheering crowds and the wide-open spaces of the natural playground where he’s headed. The effect is positively galvanizing—you experience the same anticipatory excitement that Ralston feels as he approaches his destination.

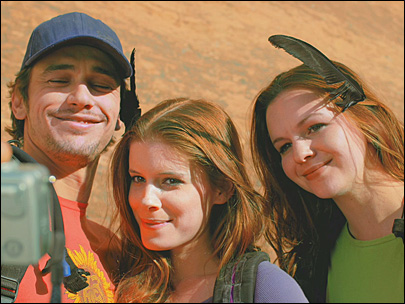

That energy increases tenfold when he hops onto his bike and tears off through the Canyonlands, a merry adventurer with no deeds to do or promises to keep. He’s drunk on the freedom of being alone in the wild; even when he takes an accidental header off his bike, he sits up laughing. After all, getting banged up is part of the fun. Coming across a pair of comely co-ed hikers (Amber Tamblyn and Kate Mara, making the most of their limited screen time), he attempts to pass on his geeky enthusiasm for the great outdoors, guiding them to a special underground pool that no hiking guide will tell you about. After that brief dalliance, he’s back on his own, scrambling through a gorge when suddenly he puts his weight on the wrong rock and tumbles down into a crevasse. He lands at the bottom and the stone crashes down on his right arm, pinning him in place. At that moment, the momentum of the previous twenty minutes comes to a sudden halt and we’re stranded there alongside Aron for the remainder of the movie as he desperately attempts to free himself before succumbing to starvation and dehydration.

Prior to the film’s release, many wondered how Danny Boyle was going to make a full-length feature about a guy trapped in a canyon. The thing is, it’s not as difficult a feat as you might imagine. There are numerous narrative devices—flashbacks, hallucinations and the like—that a filmmaker can use to flesh out what would seem to be a thin narrative to hang a movie on. And indeed, Boyle does employ many of these elements during 127 Hours, but he not in a way that feels like egregious padding. Take the flashbacks; another filmmaker might have adopted a This Is Your Life approach, boiling down Ralston’s personal history to a series of key moments, like the first time he put on a pair of hiking boots or the time his dad bought him his first Swiss Army Knife. But Boyle does something far more interesting with the flashbacks. Instead of fully-formed scenes, they are presented as abbreviated moments that appear with no exposition or explanation. Furthermore, they are always triggered by something that’s happening to Ralston in the present. For example, when his free hand is briefly bathed in a patch of sunlight, he remembers a random moment from his childhood when his dad woke him early in the morning so they could watch the sunrise together. The tactile nature of the transitions from the present to the past make these glimpses of Aron’s life seem like living memories rather than scripted flashbacks. (The closest thing we get to a narrative arc in these flashbacks are brief glimpses of the beginning, middle and end of a relationship Ralston had with an ex-girlfriend, who breaks up with him for some of the same reasons that landed him in his current predicament—namely, his lack of foresight and a pronounced loner’s streak.) And as the days pass and his condition worsens, Boyle allows memory bleeds over into reality, which results in the climactic hallucination—or, if you prefer, premonition—that leads Aron to take drastic action in order to escape certain death.

That drastic action has been well documented since Ralston’s story was first reported back in 2003, so I don’t think that it’s a spoiler to reveal that he ultimately frees himself by sawing off his own arm with a dull blade. In fact, some moviegoers might thank me for revealing that particular detail, as it’ll allow them to steel themselves for what is an almost unbearably tense and harrowing scene. The anticipation of his self-amputation is almost worse than the actual procedure—I fully admit to cringing in my seat as Ralston twists his trapped arm until it snaps. Once he’s free, Boyle wisely resists the urge to belabor the story any further; Ralston is found by another set of hikers and airlifted to the nearest hospital. A closing coda depicts Franco leaping into a pool and surfacing to come face-to-face with the real Ralston. It’s probably an unnecessary flourish, but it plays wonderfully onscreen, sending the audience out of the theater with the same sense of elation they felt in the opening scene. (It’s worth mentioning as well that this is a terrific showcase for Franco, who handles everything Boyle throws at him with aplomb.) Trim and focused without an ounce of narrative fat, 127 Hours is a thrillingly immersive viewing experience, not unlike Trainspotting all those years ago. Please Mr. Boyle, let’s have more films like this and fewer like Slumdog Millionaire…even if that’s the one that won you the Oscar.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Fair Game

Directed by Doug Liman

Screenplay by Jez Butterworth and John-Henry Butterworth

Starring Naomi Watts and Sean Penn

***

I don’t have that much to say about Doug Liman’s Fair Game, an eminently watchable, but curiously muted dramatization of the Valerie Plame affair. As you may recall, Plame was the CIA agent whose cover was blown in 2003 by officials within the George W. Bush-run White House as retaliation for an article her husband—former ambassador Joe Wilson—wrote accusing the administration of manufacturing a major piece of evidence they used to make the case for invading Iraq. The ensuing fallout cost Plame her job (and severely compromised the various international operations she was involved in), severely damaged Wilson’s reputation and almost ruined their marriage. (As for the officials responsible for the leak—that would be Scooty Libby and Karl Rove—one was tried and convicted, but had his jail sentence commuted at the president’s behest, while the other escaped prosecution and is currently a well-paid Fox News analyst.) The couple went on to write separate books about their experience, which both serve as the source material for the Fair Game screenplay, written by Jez and John-Henry Butterworth. Liman previously tried his hand at a ‘70s thriller with his adaptation of The Bourne Identity and this one feels very much like his attempt at replicating one of that era’s political procedurals such as All the President’s Men. Certainly all the elements for success are there—you’ve got a pair of supremely skilled leads, Sean Penn and Naomi Watts, playing Wilson and Plame; a smart, serious-minded screenplay that smoothly assembles all the real-life details into a traditional three-act narrative; and suitably low-key direction that gives both the political and domestic aspects of the case equal weight. So why does Fair Game never quite catch fire? Maybe it’s because, seven years on, the story lacks a sense of immediacy (unlike All the President’s Men, which hit theaters less than two years after Nixon resigned). Or maybe it’s because we’re already so inured to tales of Bush-era malfeasance, the details of the Plame scandal no longer seem shocking. But the mostly likely explanation is that the film rarely feels like anything more than a slightly better-than-average re-enactment. Fair Game chugs along dutifully recounting the events that led up to and followed the revelation of Plame’s identity, but never challenging the audience to really think about the story they’re being told or the way the film is telling it to them. It’s a modestly effective, but entirely superficial re-telling of yet another unpleasant chapter in recent American political history.

127 Hours and Fair Game both opened in limited release on Friday and will expand to more cities in the next few weeks.

No Responses to “ A Farewell to An Arm ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.