Wed 20 Oct 2010

I’m Looking For Answers From The Great Beyond

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on I’m Looking For Answers From The Great Beyond

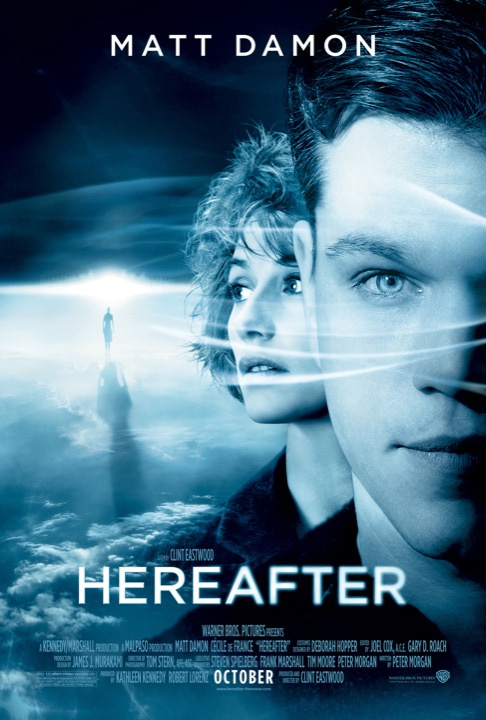

Hereafter

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Peter Morgan

Starring Matt Damon, Cecile De France, Bryce Dallas Howard, Frankie McLaren, George McLaren

**

At some point in their career, almost every filmmaker feels the urge to explore issues of mortality and what exactly happens after we die.

One of my favorite recent films on the subject is Robert Altman’s 2006 swan song, A Prairie Home Companion, in which the director took Garrison Keillor’s popular radio show and used it as a framework to craft a heartfelt farewell letter to show business. The movie has a few magical flourishes—most notably the appearance of Virginia Madsen as an angelic lady in white who hovers about the frame observing the action and greeting people when its their time to move on—but overall its attitude towards death and dying is distinctly down-to-earth. “The death of an old man is not a tragedy,†Madsen’s character says at one point, summing up the film’s point of view. Everything ends, be it a long-running radio broadcast or the life of a singer, actor or filmmaker. The important thing is to take pleasure in the world while you can and leave something behind that brings that feeling to others. (It’s a downright sentimental message from a director whose films are often considered—sometimes quite rightly—as mean and caustic, but you can tell that Altman means it.) The sweet simplicity of A Prairie Home Companion stands in marked contrast to another death-obsessed movie that came out later that year, Darren Aaronofsky’s The Fountain, which told an era and genre-spanning story of a scientist’s attempts to save his dying wife. Raiding elements of Mayan theology and Kubrickian science-fiction, Aaronofsky made a film that’s visually arresting, but rather half-baked in its philosophy about what lies in wait for us out there in the great beyond. Given the choice between Altman’s gentle depiction of death and Aaronofsky’s flashy sound-and-light show, give me Altman any day.

With Hereafter, octogenarian director Clint Eastwood takes on this tricky subject matter and comes up with a movie that’s halfway between A Prairie Home Companion and The Fountain, though overall it trends more towards the latter (minus the visual pyrotechnics) than the former. There are isolated scenes here that depict the pain and sadness that accompanies the death of a loved one with bracing, low-key honesty. Unfortunately, they are almost drowned out by the laughable pabulum and logical inconsistencies that suffuse the rest of the picture. In recent interviews, screenwriter Peter Morgan has indicated that Eastwood filmed the first version of the script he turned in without insisting on any alterations, which explains why the finished product so often feels like an early draft of a movie that’s in dire need of further revision.

Employing the same interlocking narrative structure (I believe the official online name for this sub-genre is “hyperlink cinemaâ€) that’s become so popular these days, Hereafter follows three separate story threads that eventually weave their way together in the closing moments. In the first, a French journalist (Cecile De France) has a near-death experience after a tsunami rips through the Caribbean resort where she’s vacationing and catches a glimpse of what she comes to believe was the afterlife—a shadowy landscape populated by spectral beings. The second involves a San Francisco-based psychic (Matt Damon) who can communicate with individual spirits in this realm, but loathes using his gift. The third features a young boy in England who loses his identical twin brother (played by real-life identical twins Frankie and George McLaren) in a traffic accident and can’t accept the fact that he’s gone. The latter storyline is easily the most affecting and full-developed of the three as the boy’s inability to get past his sibling’s death understandably leads him to make decisions that hurt his own life.

But the film’s single best scene involves Damon’s character, who, in an effort to have a more normal life, signs up for a cooking class where he meets a pretty girl (Bryce Dallas Howard) that seems genuinely into him. One evening after class she invites herself over for dinner and they seem to really be hitting it off…until the subject of his otherworldly powers comes up. Instantly, his date insists on a reading, despite Damon’s warnings that it will immediately short-circuit any hope they have of starting a relationship. She doesn’t back down though and he reluctantly gives in; taking her hands, his mind flashes to the other side and he locates her dead mother and father, who has a message for her about an unspecified (but easily intimated) past transgression. Just as he predicted, when the session is done, she can barely bring herself to look at him. Hurriedly gathering her things, she exits his apartment and his life, never to be seen again.

This sequence works because it’s rooted in recognizable human behavior—her curiosity about him and his desire not to lose her—and then pits the characters’ rational behavior against something irrational. That conflict is precisely what’s missing from the rest of Morgan’s script, which increasingly leans on the irrational as it progresses. Particularly in the second half, the film requires its characters to act in illogical ways and the world around them stops resembling any kind of a believable reality. Poor De France suffers the most from this as the movie turns her into a kind of spiritual detective dedicated to exposing the truth about life after death, a mission that eventually sends her to a private hospital in Switzerland, where a doctor presents her with a box of files that “prove†there really is a heaven and this information is being suppressed by the rest of the scientific world. (Instead of promptly investigating the shady institution’s credentials, this supposedly seasoned journalist accepts the doctor’s testimony on face value.)

Beyond its dubious depiction of scientific institutions and investigative journalism, the film is equally clumsy at presenting such ordinary things as book publishing, cooking classes and even basic Internet searches. (The scene where the young kid does a Google search for psychics is rife with unintentional comedy, as is a climactic scene at a book expo that more closely resembles a Saturday Night Live sketch.) It would be one thing if Hereafter was more clearly meant to take place in a heightened reality, where things are deliberately just a bit off. But it seems as if Morgan and Eastwood want audiences to accept this narrative on face value, even when it’s filled with obvious errors and stilted, contrived interactions between characters. Worst of all, the movie ultimately offers very little perspective about its central subject. In Morgan and Eastwood’s vision, death isn’t a quiet goodbye or the beginning of a grand metaphysical adventure—it’s just kind of a bummer.

Hereafter opened in limited release on Friday, October 15 and expands to more theaters and cities this weekend.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Quick Take

Punching the Clown

Directed by Gregori Viens

Written by Henry Phillips and Gregori Viens

Starring Henry Phillips, Ellen Ratner, Wade Kelley, Matt Walker

**

In a world that already has two seasons of Flight of the Conchords in it, do we really need another satirical tale of a folk singer whose tunes are more Weird Al Yankovic than Pete Seeger? Not really, and the new indie comedy Punching the Clown doesn’t do anything to prove otherwise. Co-written by and starring real-life singer/songwriter/comedian Henry Phillips, the movie follows a traveling troubadour named—what else?—Henry Phillips as he tries to make a go of a professional recording career in Los Angeles. At first, he enjoys a series of (accidental) successes, securing an agent (granted, she’s strictly small-time), nabbing a prime performance spot at a local coffee house (granted, it’s an open-mic kind of place) and even landing a recording contract with a major label (granted, the label doesn’t like him all that much). But, just as in every Hollywood-told tale of a talented musician, his semi-meteoric rise is followed by an even greater fall; thanks to a series of misunderstandings that resemble a rejected storyline from Larry David’s stellar HBO series Curb Your Enthusiasm (which is an obvious influence on the film in more ways than one), Henry is branded an anti-Semite and flees town once again for the relative comfort and safety of life on the road. The fickleness and absurdity of life in L.A.’s entertainment industry has been skewered more effectively in a number of other movies—The Player and The Big Picture to name a few—but Punching the Clown does nail a few funny observations about the business, like an early scene at a tony deck party where various revelers try and fail to catch the attention of people higher up the food chain than themselves. Overall though, the movie lacks the wicked bite of Curb and the off-the-wall zaniness of Conchords. It doesn’t help that Phillips’ self-penned songs are largely a mixed bag—some inspire some real chuckles, while others traffic in trite, obvious humor. Certainly none of them are as inspired (or as instantly hummable) as such Conchords classics as “Inner City Pressure†and “Something Special for the Ladies.â€Â He’s not even as inventive as Dan Bern, an actual folk singer who laces many of his songs with trenchant humor. If Punching the Clown is meant to persuade us that Phillips deserves to be a star, I can’t say that I was sold.

Punching the Clown opens in New York on Friday.

No Responses to “ I’m Looking For Answers From The Great Beyond ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.