Fri 17 Sep 2010

Quick Takes

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Quick Takes

Jack Goes Boating

Directed by Philip Seymour Hoffman

Screnplay by Bob Glaudini

Starring Philip Seymour Hoffman, John Ortiz, Amy Ryan, Daphne Rubin-Vega

***

Philip Seymour Hoffman makes his directorial debut with a piece that he previously starred in (but didn’t direct) for his New York-based theater company, Labyrinth. In fact, all but one of the original stage cast reprise their roles for the big screen version, including John Ortiz, who co-founded Labyrinth with Hoffman, and Broadway veteran Daphne Rubin-Vega, best known for originating the role of Mimi in Rent. The new girl on the block is Amy Ryan, but you’d never guess that based on the easy rapport she has with her co-stars. The story is yet another variation on the classic Marty scenario—a schlubby, socially awkward guy named Jack (Hoffman) attempts to reform himself to win the heart of an equally odd gal, Connie (Ryan). In this case, reforming himself means learning how to swim (so that he can take his would-be girlfriend boating, of course) and mastering the fine art of cooking so that he can present her with her first home-cooked meal.

This tale of two people falling in love is contrasted with the story of two people falling out of love, specifically Jack’s best friend Clyde (Ortiz) and his wife Lucy (Rubin-Vega), whose marriage is on shaky ground due to past affairs and other tensions. Behind the camera, Hoffman and screenwriter Bob Glaudini (working from his own play) aim for an offbeat comic rhythm that’s difficult to adjust to at first—it’s like a stilted, studied version of a Hal Ashby comedy. But as the narrative progresses, things loosen up somewhat and the skilled ensemble mines the slight material for laughs and, ultimately, some surprising emotional heft. As directorial debuts go, Jack Goes Boating doesn’t exactly herald the arrival of a major new filmmaking talent, but it does act as a modestly entertaining showcase for a group of versatile performers.

Jack Goes Boating opens in limited release today.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

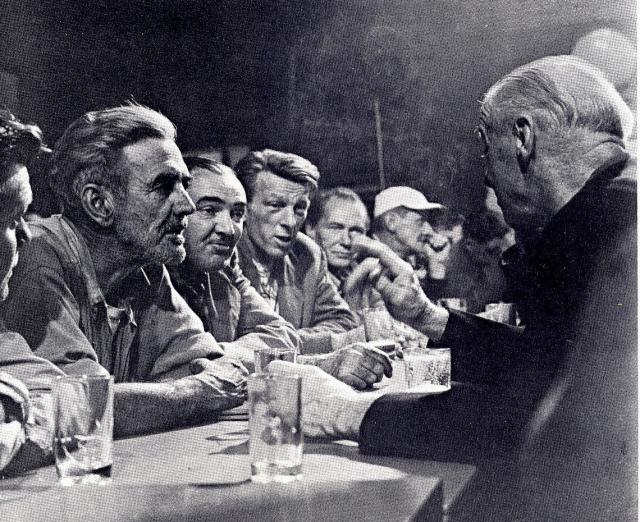

On The Bowery

Directed by Lionel Rogosin

****

With the current debate raging over the authenticity of such supposed documentaries as I’m Still Here and Catfish, it seems like a good time to revisit Lionel Rogosin’s 1957 film On the Bowery, which was nominated for the Best Feature Documentary Oscar at the 30th Academy Awards. Of course, the movie isn’t really a documentary—at least, not as how we’ve come to define the genre—and the director never insisted that it was. Instead, it’s an American version of an Italian neo-realist film; like Roberto Rossellini (Paisan) and Vittorio De Sica (The Bicycle Thieves), Rogosin built a narrative around real people and real locations. Taking his camera downtown to Manhattan’s Bowery, the filmmaker shot in actual residents in the bars and flop houses they frequented on a daily basis. Though the movie’s story—which revolves around a Bowery newcomer hopping of the subway flush with cash only to end up drunk and destitute—spans only three days, shooting actually took months as Rogosin encouraged his “actors†to improvise all of their dialogue and routinely had to shut down production to raise more money. Seen today, On The Bowery offers a vivid portrait of a New York that’s long since vanished (or, some might argue, has simply moved further uptown). It’s no surprise that audiences at the time considered it a documentary—compared to the fantasies they were getting from Hollywood, it’s practically cinema verite, which, of course, would come along not too long after the picture’s release. One of the things that I found most interesting about viewing the film from a contemporary perspective is how unpolished and uncertain the performances are. In this age of reality television, everyone is comfortable–perhaps too comfortable–with the idea of being filmed. At the time Rogosin made his film though, ordinary people weren’t necessarily accustomed to being on, let alone performing for, a camera. The cast’s visible discomfort actually enhances their screen presence in a curious way; they aren’t out to sell us on an image of themselves, they’re just trying to be who they are in daily life. Some contemporary documentaries approach real life in the style of fiction; On the Bowery uses fiction to explore real life.

On The Bowery opens at New York’s Film Forum today for a one-week engagement. It will open in additional theaters in October.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Last Day of Summer

Written and Directed by Vlad Yudin

Starring DJ Qualls, Nikki Reed, William Sadler

*1/2

I’m not quite sure what feelings writer/director Vlad Yudin hoped viewers would take away from his first narrative feature (he previously helmed a documentary about the rapper Big Pun), but chances are it wasn’t shock at the inanity of the film’s plot or pity for the actors stuck in this mess. Set over the course of, as the title states, the last day of summer, the movie follows disgruntled wage slave Joe (DJ Qualls) who decides that the best way to take revenge on the many people who have heaped abuse upon him—most notably his asshole boss (William Sadler) at the fast food franchise where he toils—is to buy a gun and shoot them all. Before he can put his ill-advised plan into action, he exchanges looks with the comely Stefanie (Nikki Reed), a moment he misinterprets as a flirtation. When she quite firmly insists otherwise, he kidnaps her at gunpoint and takes her back to his motel room because…well, because he’s really not all that bright. Apparently Stefanie isn’t the sharpest knife in the drawer either though, because she proceeds to befriend this deeply disturbed kid and even encourages his sense of victimization. Yudin can’t seem to make up his mind how he feels about his main character either; on the one hand, he goes out of his way to make the audience sympathize with a would-be murderer, but he also takes pleasure in staging his various humiliations. Meanwhile, his script careens wildly between comic moments that aren’t funny and dramatic moments that are preposterous and banal. In the end, the only convincing life lesson Last Day of Summer has to offer is this: Don’t piss off the janitor at your local Mickey D’s.

No Responses to “ Quick Takes ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.