Thu 15 Jul 2010

Mind Games

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Mind Games

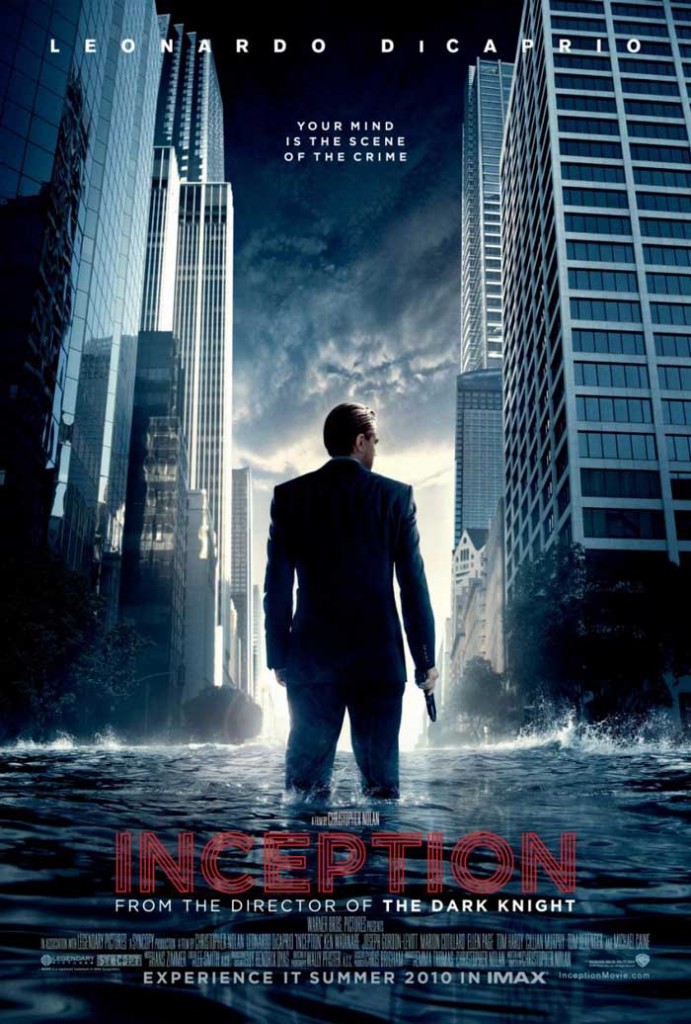

Inception

Written and Directed by Christopher Nolan

Starring Leonard DiCaprio, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Ellen Page, Tom Hardy, Ken Watanabe.

***

Heist movies are only as good as their climactic heist and in Inception, writer/director Chris Nolan comes up with an ingenious one. Seizing on the gimmick of dreams Nolan stages a heist that takes place across four different dreamscapes, including a rain-soaked city, a posh hotel, a remote mountain bunker and, last but not least, a crumbling metropolis that exists on a level of dreaming that’s referred to in grave tones as “limboâ€â€”a place from where few who venture ever return.

Actually, it’s not entirely accurate to call the mission at the heart of the movie a heist, as that implies that something is being stolen. Instead, team leader Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his five-person squad are breaking into a secure facility—in this case a man’s mind—in order to leave something behind, specifically a small suggestion that they hope will flower into an idea and, eventually, a specific course of action. The process is called “Inception†and it’s the opposite of the job Cobb normally performs, “Extraction,†where he locates and lifts secrets from the dreamer, typically high-powered tycoons eager to protect crucial business details from their rivals.

To pull off this high-risk assignment—which, as always in a heist movie, is gonna be the hero’s “last job†before his retirement from the game—Cobb assembles a team that includes his second-in-command Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), gifted mimic Eames (Tom Hardy), sedatives expert Yusuf (Dileep Rao) and a new recruit, gifted architectural student Ariadne (Ellen Page) who is tasked with designing the various dreamscapes or “levels†that their “Inception†plan will play out in. Also along for the ride is Cobb’s employer Saito (Ken Watanabe), a wealthy businessman who insists on following them into the mind of their target—the heir to a giant energy conglomerate (Cillian Murphy). You should also know that Cobb is literally haunted by the memory of his dead wife Mal (Marion Cotillard), who wanders into these carefully constructed dreams and wreaks havoc. Oh yeah, and it’s also entirely possible that Cobb is dreaming the whole time and none of what we see is “real.â€Â Cue The Twilight Zone theme…now!

And that’s really all I’m prepared to reveal about the plot. It’s not just that I want those of you that see the movie (and I do hope that most of you see this movie) to experience Nolan’s twisty narrative on your own terms, but summarizing every relevant or even semi-relevant plot point would take an entire afternoon. More than any other A-list director working in Hollywood today, Nolan is obsessed with twisting and re-shaping traditional storytelling structures. That fascination dates back to his first two films—Following and, of course, Memento—and he’s continued to explore it in at the studio level in movies like The Prestige and this one, which conveniently fall between blockbusters like Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

It’s not a stretch to say that Inception is the movie that Nolan has been building to since Memento. Not only has he admitted to spending the decade since his 1999 breakthrough honing the Inception script, but he needed to cut his teeth on more conventional movies like Insomnia and the Batman franchise in order to successfully pull of the mixture of large-scale action and narrative gamesmanship that this enterprise demands. The wait paid off; Inception is perhaps Nolan’s most-confidently directed picture to date, particularly in the second half when the heist is sprung and he cuts back and forth between four radically different environments and a multitude of storylines as effortlessly as if he’s directing a simple two-hander about two guys having lunch at a coffee shop. (Of course, a large amount of credit must also go to his longtime editor Lee Smith, who must have logged many long hours in front of the Avid constructing the movie’s complex editing scheme.)

One of the keys to enjoying Inception, at least for me, was accepting that Nolan isn’t all that interested in really exploring the form and content of dreams in the same way that directors like David Lynch, Michel Gondry and Joss Whedon (whose “Restless†episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer remains one of the best dream stories I’ve seen on the big or small screen) have in their dream-inspired works. For one thing, as other critics have already pointed out, there’s apparently no such thing as sex in Nolan’s conception of dreaming. Even Cotillard, one of the most beautiful actresses working today, gives off very little heat here. (To be fair, that is partly by design as her presence is meant to unnerve Cobb, not turn him on.) There are also few of the wild shifts in tone that you get in movies like The Science of Sleep or Mulholland Dr. or, for that matter, in your own dreams which can change on a dime from pleasant to nightmarish.

Then again, as the movie continually reminds us (one of Nolan’s weaknesses as a writer has always been his tendency to make his characters repeat information over and over again) these aren’t normal dreams. Rather, they are artificially constructed environments that are “downloaded†into the target’s subconscious during sleep and peopled with avatars drawn from his memory, which turn against interlopers like Cobb and his team when the cracks in their “reality†start to show. Forget dreams—Inception’s worlds are more like the levels of a video game, an idea that’s driven home in an early scene where Page tries her hand at designing a level, creating bridges over freeways and conjuring mirrors out of thin air. It’s like watching her play a live-action version of a do-it-yourself game like Sim City or LittleBigPlanet. Many of the wild-action sequences that Nolan stages also feel video-game ready, most notably a terrific gravity-challenged fight in a hotel hallway that moviegoers will be talking about for the rest of the year. Don’t be surprised if you start hearing people using some of the film’s invented terminology in casual conversation as well. Since seeing Inception, I know that I’ve personally fought the urge to say “Man, I kept waiting for the kick to tell me to wake up from that crazy dream†every morning. (That sentence will make more sense after you’ve seen the film.) That’s a testament to how cleverly Nolan has constructed Inception’s peculiar take on the science of sleep, as well has how effectively he appropriates video game aesthetics—once you understand the ground rules, the movie’s universe is as immersive and addictive as any massively multiplayer online game.

If Inception plays quite well as a heist movie and a feature-length brain-teaser, I’m not convinced (at least after one viewing) that it’s all that interesting as a psychological drama. Maybe it’s just because the movie is arriving in theaters on the heels of Shutter Island, where DiCaprio also played an emotionally damaged guy torn up about the death of his somewhat insane spouse, but I never found the Cobb-Mal relationship all that convincing or compelling. It’s a necessary plot device as without it, Nolan can’t toy with the “Is it all a dream?†question he returns to throughout. But in the end, that’s all Mal represents to me—a plot device. (It may also be due to the fact that Nolan has gone to the “dead wife/girlfriend†well once too often: see Memento, The Prestige and The Dark Knight. If I were Mrs. Nolan, I might start to be a bit concerned.)

The same goes for most of the supporting characters, few of whom have any discernable personality. That’s par for the course in most heist movies, where team members are defined by their function first and their personal quirks second. It’s typically up to the individual actors to find ways of giving the audience a sense of who these characters are when they’re off the clock. In Inception, the only performers that come close to accomplishing this are Gordon-Levitt and Hardy, who play their roles with a wry sense of humor that helps offset the overbearing seriousness that often threatens to smother the movie. Watanabe, Page and Rao aren’t as successful, which is not to say that they’re bad—they just can’t find a way around the limitations the script places on them. Page in particular gets the short end of the stick, as Adriane’s primary function is to serve as the bullhorn through which Cobb explains the team’s rules of engagement to the audience. As for DiCaprio, he scowls like a champ and delivers Nolan’s heavy-handed dialogue with panache, but Cobb is largely a one-note presence. Whatever its flaws (and it had its fair share), Shutter Island allowed DiCaprio to play a character who wasn’t purely defined by a guilty conscience.

In the run-up to Inception’s release, firm battle lines have been drawn over whether the movie is some kind of Kubrickian masterpiece or an overpraised bit of big-budget flimflam. As boring as it is to play Switzerland in this war of words, I think both sides are profoundly overstating their case. Inception certainly ranks as an impressive technical achievement and is easily among this summer’s most absorbing blockbusters (which, granted, isn’t a very long list). But it isn’t a personal best for Nolan, who seems to have grown more distant from his material as his budgets have swelled. His intense interest in the mechanics of filmmaking is commendable and you can see obvious growth from his first studio picture, Insomnia, to this one. At the same time though, he’s lost some of the playfulness and narrative economy that distinguished Memento all those years ago. His grasp on characterizations has also slackened significantly; too many scenes here involve Cobb and his team talking at each other in almost bullet-point form, outlining or reiterating plot points instead of engaging in more revealing and personal conversations. (And that’s one of the many reasons why comparisons to Kubrick seem off-base to me; among his many talents, Kubrick was always very exacting and precise with dialogue, whereas Nolan often overwrites to an absurd degree.) It’s as if Nolan views the people in this movie primarily as chess pieces—or, to be more current, video-game avatars—to be moved around as the narrative structure he’s carefully constructed demands. As a result, Inception is often thrilling to watch, but there’s something hollow at its center.

Inception opens in theaters tomorrow.

No Responses to “ Mind Games ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.