Thu 27 May 2010

Two Artists Walk Into a Cinema…

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Two Artists Walk Into a Cinema…

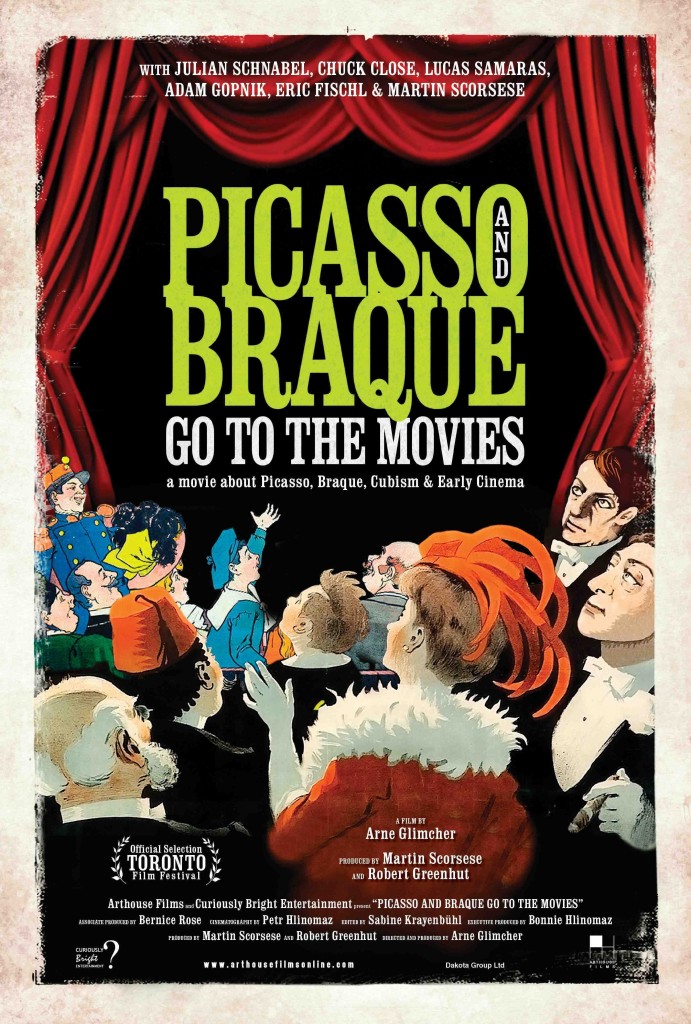

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies

Directed by Arne Glimcher

***

Film has been the dominant form of mass art and entertainment for so long it’s difficult for contemporary audiences to conceive of a time when the very idea of “moving pictures†seemed incredible.

Sure, movies still have the power to dazzle us—witness the next-gen images in James Cameron’s Avatar or the small-scale beauty of a slice-of-life tale like Shotgun Stories—but we’re no longer surprised by our ability to sit in a dark room and watch a series of moving images that have been assembled into some kind of narrative play before us on a big screen. One of the strengths of Arne Glimcher’s new documentary Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies is that it effectively chronicles an era when going to the movies was a novelty, one that would quickly prove to have a profound impact on the way we observe other kinds of visual art and the way artists themselves create that art.

Glimcher’s briskly-paced doc spans a little over a decade in the history of early cinema, from the late 1890s right up to the start of the first World War in 1914. As the title implies, the narrative is anchored around two painters whose work came to be heavily influenced by their frequent trips to the movies: Pablo Picasso and Gorges Braque. Friends and colleagues, both men were living in turn-of-the-century Paris when that city first went movie-mad. In addition to standalone cinemas that populated almost every neighborhood, films could be seen in music halls, after-hours cabarets like the Moulin Rouge and even department stores. Since the ability to produce full-length features was still years away, these movie houses played programs of shorts that ranged from scenes of everyday life to travelogues to slapstick-heavy comedies to the fantastical imaginings of director George Méliès, the man behind the famous 1902 picture “A Trip to the Moon†probably the first science-fiction film ever made.

But the content of the movies themselves was almost beside the point; what captivated audiences, particularly viewers like Picasso and Braque, was the medium itself. Beyond the simple fact that the images moved, film offered a way to manipulate concepts of time, space and distance in a way that no other art form had before. In a sense, this period of film history functioned as an extended clinical trial during which filmmakers were running ongoing experiments to determine what the medium was capable of. As Martin Scorsese—who produced the documentary and is among the subjects interviewed on camera—points out, these shorts were inventing cinematic language on the fly. For instance, the first films were all shot from a fixed perspective without any cuts to close-ups or medium shots because it was assumed that viewers wouldn’t know they were watching the same person from shot-to-shot. (Yes, film companies were underestimating the audience’s intelligence even back then!) But that quickly changed as directors like Méliès grew more ambitious in their attempts to tell a story rather than simply document an event or a pratfall. And, as it turned out, the close-up has arguably become the most important tool in a filmmaker’s toolbox. Picasso himself was purportedly a big fan of the shot and integrated it into his paintings, albeit filtered through a Cubist lens.

In addition to Scorsese, Glimcher’s documentary also features interviews with a handful of film historians like the University of Chicago’s Tom Gunning and several art-world notables including art history professor Natasha Staller and painters Chuck Close and Julian Schnabel. It’s a rich list of talking heads and, if anything, Glimcher doesn’t exploit their knowledge and insights enough. Maybe it’s just because of its short runtime (62 minutes) or maybe it’s the strictly regimented focus on the two titular artists, but Picasso and Braque Go the Movies feels like the middle section in a longer documentary about cinema’s origins. And, to be honest, at times Glimcher struggles to connect Picasso and Braque to film’s evolution as a medium for artistic expression and creativity. That material just seems less interesting when you have Scorsese discussing his efforts to channel Méliès while shooting the final scene of The Departed or Gunning describing the popularity of Sally Rand’s filmed Fan Dance with early 20th century audiences. Picasso and Braque may have been Glimcher’s entry point into early cinema history, but a subject this extensive cries out to be painted with a broader brush.

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies opens the Cinema Village theater in New York on Friday.

No Responses to “ Two Artists Walk Into a Cinema… ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.