Tue 11 May 2010

Do The Robot!

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Do The Robot!

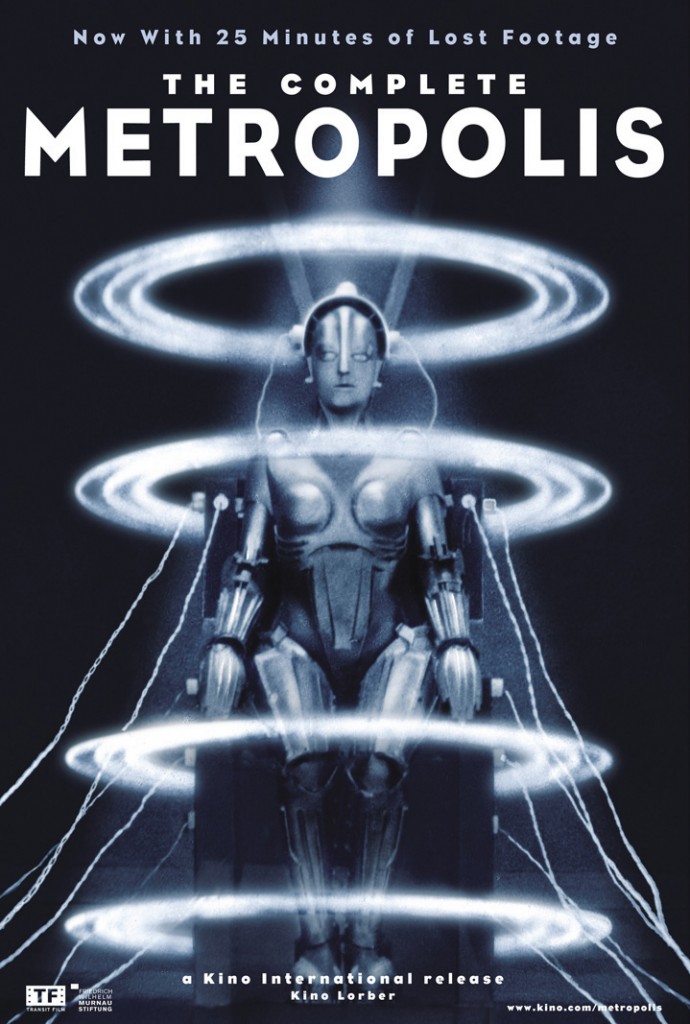

Metropolis

Directed by Fritz Lang

****

My first viewing of Fritz Lang’s landmark 1927 film Metropolis happened sometime in the early ‘90s via an unassuming VHS tape (remember those?) that lived in my family’s home video collection. Presentation-wise, I couldn’t have asked for a worse way to see the film for the first time. The transfer was sub-par resulting in images that were scratched and faded, the intertitles were barely legible and because it was one of those EP video cassettes (that’s “extended play†to anyone born after 1995) I was constantly fiddling with the VCR settings to get the movie to play at the right speed.

Despite all those distractions, Metropolis still cast its strange spell over me, which is a testament to Lang’s tremendous imagination. You only need to see Metropolis once to realize how completely its forward-thinking visuals have influenced virtually every futuristic science-fiction film made since, from Blade Runner to The Matrix to the Star Wars prequels, to say nothing of other popular entertainments like Tim Burton’s Batman. But the future Lang created onscreen remains entirely compelling on its own terms. His fictional metropolis’ towering skyscrapers can barely be contained by the screen, stretching on almost endlessly into the heavens. In the shadows of these buildings, automobiles putter along elevated causeways and small airplanes soar through the air at a disturbingly low altitude. The city appears to be an absolute triumph of engineering and human endeavor, a self-made paradise only achievable by our minds and hands.

Because there’s no such place as Utopia though, this metropolis does have its dark secrets, most of which are buried deep underground where the men and women that built the city are forced to work long hours wrestling with the machines that keep it running. Lang’s grim vision of an assembly-line underworld is far more disturbing than the usual fire-and-brimstone model, if only because it seems closer to reality. It’s difficult to shake the images of robotic workers shuffling on and off their cattle-car elevators or mindlessly pushing buttons, twirling knobs or raising and lowering levers. For many (myself included), the film’s most memorable scene features that lowly worker tasked with maintaining what appears to be some kind of enormous temperature dial. As he frantically turns the hands on the dial’s face this way and that, the sheer pace of the job eventually overwhelms him and he sinks to the floor seemingly unable to rise again.

Since that first viewing of Metropolis, I’ve revisited the movie a number of times, initially on that same awful VHS tape before thankfully graduating to big-screen screenings at film school. It’s worth noting that all those viewings were of the severely truncated 90-minute version (though not the one scored to Queen) of Lang’s original two-and-a-half hour movie because, at the time, that was the only iteration that was readily available. (Other folks have chronicled the long, strange saga of Metropolis more extensively than I could. Articles like this one and this one illuminate how much this film has been through over the decades.) But that changed with the 2001 release of a restored cut that clocked in at just over two hours and which played theatrically in such first-rate movie houses as New York’s Ziegfeld Theater (where I saw it along with a small, but devoted audience of film buffs). That cut re-edited the storyline to more closely follow Lang’s vision and dropped in detailed descriptions of scenes that were still missing. It was the closest many assumed we were going to get to a fully restored version of Metropolis…that is, until reels of Lang’s original cut turned up in Buenos Aires in 2008.

After an extensive restoration process, all of the previously missing material (well, almost all–two crucial scenes still remain at large) has been worked back into the movie, giving us a version of Metropolis that deserves its billing as “completeâ€Â Currently playing at New York’s Film Forum, the movie will take a victory lap to other select U.S. screens before arriving on DVD later this year. While the disc is obviously a must-own, Metropolis demands to be seen on the big screen. Leaving aside the new sequences for a moment, this version offers the best presentation of the existing material that I’ve seen to date. The images are astonishingly crisp and sharp, allowing the audience to really see at the level of detail Lang and his production team worked into the lavish sets. There were a number of moments where I felt as though I were seeing the movie for the first time instead of the fifth or sixth.

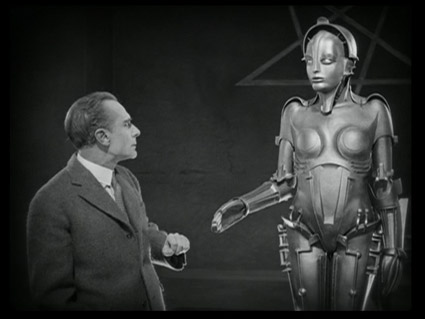

Unfortunately, the restored material isn’t integrated as seamlessly into the movie as you might hope. Because the recently discovered print was not stored in optimal conditions, the missing scenes are set apart by their obvious wear and tear and as well as a vaguely letterbox-style presentation, a result of the difficulty in transferring the sequences from 16mm back to 35mm. In a way though, it’s helpful to be able to see so clearly what exactly has been added to the movie. To be honest, none of the new material drastically affects the film’s overall tone or narrative, which, for the uninitiated tells the story of Metropolis’ overseer John Fredersen and his rebellious son Freder, who joins a working-class uprising after falling in love with Maria, the beautiful woman whose words and wisdom inspire all those that toil underground.

Instead, these sequences enhance details and answer questions that were glossed over in the abbreviated cut, such as “Who is that weird-looking guy in the fedora that Jon Fredersen keeps talking to?†(Answer: He’s Fredersen’s personal enforcer) and “What happened to the worker that Freder replaces at that giant dial-thing anyway?†(Answer: He’s instructed to rendezvous with Freder later at an apartment, but instead dances the night away at the city’s most decadent nightclub.) One of the most memorable additions comes in the climactic riot, when Freder and another man scale impossibly tall scaffolding in order to escape a rushing river of water. This sequence is all the more impressive when you remember that the actors are doing all of their own climbing on actual scaffolding—no CGI-trickery for filmmakers back in 1927!

One thing the restored scenes can’t do, of course, is improve Metropolis’ ludicrously melodramatic plot and inconsistent acting. Lang’s movie is a joy to watch, but its general dramatic clumsiness, not to mention its wide-eyed political naïveté, make it difficult to take seriously as a story or as social commentary. On the other hand, its mixture of idealism and innocence is a big part of its charm. There’s no room for irony in Lang’s universe; he firmly believes in the philosophy he’s selling, which is summed by the movie’s now-famous closing line “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart.â€Â At best overly optimistic, at worst nonsensical, this statement nevertheless captures the grand excess that is Metropolis. It’s a movie that’s all heart, even when that threatens to get in the way of its head.

Metropolis is currently playing at Manhattan’s Film Forum with additional release dates to follow. Visit the official website to read about upcoming theatrical showings and the planned DVD release.

No Responses to “ Do The Robot! ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.