Sun 25 Apr 2010

Tribeca Film Festival Dispatch #2

Posted by Ethan under Film Festivals

Comments Off on Tribeca Film Festival Dispatch #2

More reviews from the 2010 Tribeca Film Festival.

Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work

Directed by Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg

***

I’d been hearing good things about this fly-on-the-wall portrait of comedienne/fashion critic/all-around misanthrope Joan Rivers since it premiered to general acclaim at the Sundance Film Festival in January. It’s nice to report that the film mostly lives up to the hype. Smartly assembled by directors Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg, A Piece of Work places Rivers’ groundbreaking four-decade career in context for those contemporary viewers who primarily know her as a punching bag for plastic surgery jokes or as a staple on awards show red carpets. But the filmmakers don’t spend too much time dwelling on the past; instead the bulk of the movie spans a very eventful year in the now 75-year-old performer’s life, beginning with her attempts to launch a one-woman show in the U.K. with tentative plans to then open it in on Broadway (plans that are later scuttled when the reviews are weaker than she would like) and ends with her winning the NBC reality series Celebrity Apprentice. A savvy businesswoman–she refers to herself as “a brand” without a trace of irony–Rivers clearly views this film as another way to publicize her career and presents herself as a workaholic who will perform anytime, anywhere particularly if the price is right. Fortunately, Stern and Sundberg do manage to capture several moments where her public mask drops and we get a clearer sense of the “real” Joan Rivers. (Many of these moments involve Rivers’ daughter Melissa, with whom she shares a loving, but noticeably tense relationship.) Truth be told, the filmmakers seem too enthralled by their subject at times; the movie would have been more interesting had they taken a critical eye to some of Rivers’ career choices–like the notorious TV movie that dealt with her husband’s suicide in which she and Melissa played themselves–and sought out interviews with people that aren’t necessarily her biggest fans. Still, A Piece of Work is an entertaining and lively portrait of a performer whose contribution to comedy is often, and probably unfairly, overlooked.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Lola

Directed by Brillante Mendoza

Starring Anita Linda, Rustica Carpio, Tanya Gomez

***

Brillante Mendoza’s involving eighth feature plays like an extended homage to Italian neo-realist classics like Open City and The Bicycle Thief, taking a clear-eyed, ground-level look at life on the lower rungs of Filipino society. (Unlike those movies though, Mendoza mostly employed professional actors to play his down-and-out characters.) Unfolding in almost real time, the movie follows an elderly woman’s attempts to raise enough money to bury her grandson, who was recently killed in a mugging. Meanwhile, the grandmother of the alleged murderer is also trying to scrounge up enough cash to reach a settlement with the victim’s family. As they beg, barter and pawn their household wares to pay the mounting bills, these women also have to navigate a difficult bureaucracy that demands time, energy and lots of paperwork. What’s interesting about Lola is that, despite the hardships its characters endure, the movie’s worldview is never bleak. Family and friends pitch in and help whenever possible and the local government institutions do perform their functions, albeit slowly. One keeps expecting a corrupt lawyer or backstabbing neighbor to derail the characters’ plans, but that never comes to pass. While it would be wrong to characterize the film’s final moments as happy, the women do ultimately arrive at a place of mutual understanding and go their separate ways satisfied, if not wholly healed.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Monogamy

Directed by Dana Adam Shapiro

Starring Chris Messina, Rashida Jones, Meital Dohan

**

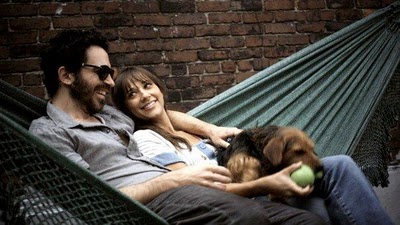

This dreary tale of a soon-to-be married couple (Chris Messina and Rashida Jones) experiencing a wicked case of cold feet has exactly one thing going for it: location, location, location. Director Dana Adam Shapiro (making his narrative debut after helming the acclaimed documentary Murderball) shot the movie largely on the streets of Brooklyn and downtown Manhattan and the local scenery gives the audience something to concentrate on besides the annoying characters and contrived drama. In an obvious nod to Michaelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 classic Blow-Up, Messina’s character is a photographer who becomes obsessed with one of his subjects, a woman who may or may not be cheating on her husband by having sex with a random guy in various public places around the city. Her apparent infidelity starts to affect his attitude towards his own impending marriage and leads him to do bizarre things, like putting on a dog mask and barking at himself in a mirror (don’t ask). Messina and Jones actually share a nice chemistry together–you believe these two have been in a loving relationship for a long time–but the ridiculous plot mechanics defeat their attempts at bringing some emotional truth to the film.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Trotsky

Directed by Jacob Tierney

Starring Jay Baruchel, Michael Murphy, Emily Hampshire, Saul Rubinek

**1/2

Jay Baruchel is a terrific comic actor still looking for the right film to put his talents to proper use. Until he finds that vehicle, he’ll have to settle for being the best thing in mediocre movies like the recent Hollywood rom-com She’s Out of My League and this Canadian-made high school satire in which Baruchel plays Leon Brosntein, a 17-year-old misfit who is convinced that he is the second coming of Communist icon Leon Trotsky. Resolute in his desire to follow in his hero’s footsteps, Leon takes it upon himself to unionize the apathetic student body at his Montreal public high school, a mission that pits him against the Stalin-esque principal of said institution. Meanwhile, he also initiates a one-sided romance with 27-year-old grad student Alexandra…the name of Trotksy’s eventual wife. It’s a promising premise, but writer/director Jacob Tierney seems unclear about what kind of film he’s attempting to make. The high school material seems heavily inspired by Alexander Payne’s deadpan Election, while the scenes depicting Leon’s home life play more like a broad sitcom. (As for the love story…well, that’s just kind of creepy.) At 114 minutes, the movie is also much too long, particularly since the pacing is so sluggish. It’s a good thing that Baruchel is compulsively watchable, because otherwise those of us in the audience might have staged a revolution of our own.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Visionaries

Directed by Chuck Workman

**

One of the most valuable classes I took in film school was devoted entirely to experimental film. Prior to that course, I tended to dismiss this entire category of filmmaking as boring, pretentious crap and, to be honest, there were a number of movies that I saw during the semester that fit that exact description. But the sheer depth and variety of films I got to see–as well as the ability to discuss and analyze them afterwards–soon showed me the error of my ways. Ideally, every regular moviegoer should have the opportunity to take an “Introduction to Experimental Cinema” class at some point during their lives. Since that’s not a likely prospect though, a documentary like Chuck Workman’s Visionaires, which profiles some of the most famous experimental films and filmmakers, would seem to be an invaluable resource. Too bad it’s such a superficial and poorly organized survey of a fascinating subject. Part of the problem is that experimental films generally have to be viewed in their entirety to truly appreciate them. Simply seeing a clip from Maya Deren’s seminal Meshes of the Afternoon or Kenneth Anger’s iconic Scorpio Rising gives you a sense of their strangeness, but not of the deeper ideas the filmmakers are trying to convey. But Workman is also to blame for not finding a stronger structure for his film. Visionaries begins with a too-brief history of experimental cinema and then speeds through segments on specific directors like Deren, Anger, Stan Brakhage and Robert Downey. Then in the final twenty minutes, the movie becomes an extended paean to filmmaker Jonas Mekas and the film collective he helped found, the Anthology Film Archives. This is not to say that Mekas and Anthology aren’t worthy of celebration; on the contrary, both are vitally important to New York film culture. But the presentation of this material is tonally out of place with the rest of the movie–it feels like the kind of career tribute you’d play at a retirement party or a funeral (which is a problem since Mekas is neither retired nor dead). Had Workman used Mekas’ career as the basic narrative skeleton for Visionaries–after all, he’s been a driving force in the world of avant-garde film for well over five decades and has personally known every experimental filmmaker worth knowing–the proceedings most likely would have been more focused, giving viewers a better sense of what experimental cinema is and why it matters.

No Responses to “ Tribeca Film Festival Dispatch #2 ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.