Thu 8 Apr 2010

Strange Days

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Strange Days

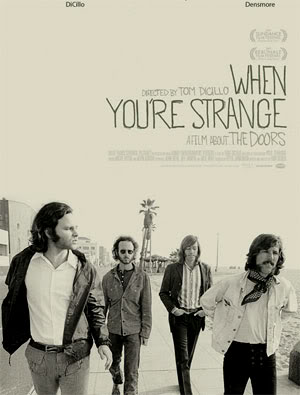

When You’re Strange: A Film About The Doors

Directed by Tom DiCillo

**

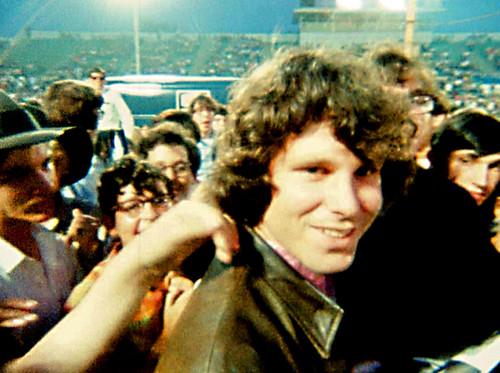

Tom DiCillo’s new rock doc When You’re Strange is subtitled A Film About The Doors, but really it’s a film about that band’s iconic frontman, one Jim Morrison, a controversial figure who continues inspire devotion and loathing in equal measure almost forty years after his death.

The singer’s fans—a group that clearly includes DiCillo, as well as Oliver Stone, who turned his 1991 Doors biopic into an extended paean to Morrison—apparently regard him as a shining beacon of artistic purity…albeit one who was drunk or drugged out (and sometimes both!) much of the time. On the other hand, Morrison’s detractors, which seems to consist of almost anyone born after 1971, frequently consider him a self-important egomaniac with dubious creative skills beyond that admittedly impressive howl of a singing voice. A truly substantive film about the Doors would spend more time probing the space between these wildly different interpretations of his legacy, while also exploring the contributions of the rest of the band. Unfortunately, When You’re Strange is not that movie. While DiCillo does pay slightly more attention to keyboardist Ray Manzarek, drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger than Stone’s biopic did, the film’s focus remains largely on Morrison. Granted, the singer certainly led a more flamboyant extracurricular life than the rest of his bandmates, but the movie is as much in his thrall as the teeming hoards of enraptured fans shouting his name in packed concert halls.

Like the recent Disney documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty, When You’re Strange is made up entirely of archival material, including photographs, home movies and even footage from a 1969 short film that Morrison directed and starred in. (In the interest of full disclosure, I should cop to the fact that I mistakenly dismissed all those scenes as poor re-enactments with a Morrison stand-in. This article set me straight—they were just scenes from a poor experimental film.) DiCillo even goes a step further than Beauty director Don Hahn and avoids interviews altogether. Instead, the only present-day dialogue hear in the movie is narration delivered by Johnny Depp, who apparently is the go-to guy for talking over documentaries about counterculture icons. (He previously lent his baritone to Alex Gibney’s Hunter S. Thompson doc Gonzo.)

DiCillo drew on a variety of first and second-hand sources to pen the voiceover that Depp oh-so-seriously intones, but it mostly sounds like material cribbed from a fanzine or two as well as a second-hand rock encyclopedia. The events of the turbulent ‘60s are duly rehashed without any new insights and the band’s own evolution from a ragtag outfit practicing in their garage to a successful super-group with a best-selling album and a crowded tour schedule is quickly rushed through. One gets the sense that DiCillo is consciously dumbing the movie down for younger viewers who know next to nothing about the Doors. While it’s understandable that he wants to pitch the movie towards the widest possible audience, he does so at the cost of alienating viewers that have heard these stories before and told with more depth and nuance then is on display here.

The narration is at its most annoying though, when it tries to analyze Morrison’s behavior or, even worse, get inside his head. It would be inaccurate to say that DiCillo apologizes for the singer’s various addictions, but he doesn’t seem overly concerned about addressing the toll they take on the band or his personal life. The film also expects us to accept Morrison’s supposed magnetism on face value; he’s regularly described as a “shamanistic figure†and other such grand terms and excerpts of his poetry are offered up like pearls of wisdom. Although the copious concert footage does reveal that, in his best, most lucid moments, Morrison possessed a considerable stage presence, few of his off-stage achievements seem worth of the kind of adulation lavished upon him here.

If the film largely fails as objective biography, it does serve a purpose as a one-stop shop for familiar, rare and even unseen Doors memorabilia. DiCillo and his team of researchers certainly deserve credit for assembling such an impressive collection of material. The film also functions as a rudimentary Doors-tutorial, rifling through the band’s catalogue (with a disappointing emphasis on the familiar tracks—no deep cuts here) and illustrating exactly how their version of rock music differed from much of what was being produced at the time. Not being a particularly big fan of the group myself, I did take away a new appreciation for Manzarek’s skills at the keyboard as well a continued affection for classic rock chestnuts like “Light My Fire†and “Riders on the Storm.â€Â (I still don’t care for the doc’s title track or “Love Her Madlyâ€â€¦sorry.) Overall though, for a film that wants to make the case that The Doors—and more specifically Jim Morrison—are an essential part of rock history, When You’re Strange is curiously inessential.

When You’re Strange: A Story About The Doors opens in limited release today.

No Responses to “ Strange Days ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.