Thu 1 Apr 2010

Animation Nation

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on Animation Nation

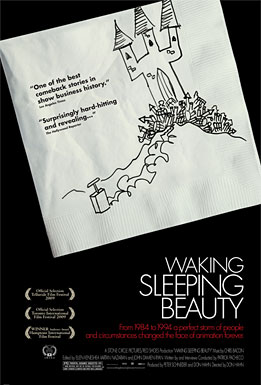

Waking Sleeping Beauty

Directed by Don Hahn

***

Since it was produced and distributed by Walt Disney Studios, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the new documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty essentially plays like a traditional Disney animated picture.

Director Don Hahn, a longtime Mouse House employee, condenses a roughly ten year period in the company’s history—from the release of The Black Cauldron in 1985 to The Lion King’s first roar in 1994—into a briskly-paced 85-minute tale about a band of plucky animators who overcame huge obstacles to achieve their goal, in this case rescuing Disney’s storied animation unit from complete creative collapse. The movie also makes room for such studio staples as broad comedy (footage of the animators re-enacting scenes from Apocalypse Now), emotional tragedy (the untimely death of lyricist Howard Ashman, the man responsible for such tunes as “Under the Sea†and “Be Our Guestâ€), musical numbers (early recordings of both of those beloved songs) and even a hissable villain (former executive Jeffrey Katzeneberg, who currently calls the shots at DreamWorks Animation). You have to give Hahn credit for crafting a movie that’s as slickly-made and eminently enjoyable as any one of Disney’s current crop of animated adventures. In that way, Waking Sleeping Beauty could be the rare kind of Hollywood expose that actually crosses over to a wide audience; it has enough behind-the-scenes gossip to delight industry watchers, but isn’t too inside baseball to alienate ordinary moviegoers.

As entertaining as I found Waking Sleeping Beauty while watching it, I have to admit that the film ultimately left me unsatisfied. Hahn succeeds at painting a broad overview of Disney’s renaissance, but he never really captures what I consider to be the most fascinating part of the story, namely the creative process that resulted in such landscape-altering hits as The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast and even interesting misses like The Black Cauldron and The Great Mouse Detective. This is especially disappointing when you consider the unprecedented access he had to the men and women responsible for making those movies. Waking Sleeping Beauty is packed with new interviews with just about every notable person you can think of from Disney’s recent history, from animators like Glen Keane to producers like Peter Schneider (who also produced this documentary) to key executives Michael Eisner, Roy Disney (Walt’s nephew and the man who championed the animation division when no one else would) and even the controversial Katzenberg himself.

In a smart directorial choice, Hahn avoids talking-head interviews, instead allowing his subjects’ comments to play over an assembly of home-movie footage (much of which was shot at the time by John Lasseter, better known today as Pixar’s head honcho), vintage TV interviews and news clips, studio-produced promotional material and, of course, lots of clips from the films themselves, both in completed and rough-animation form. In interviews, Hahn has boasted that there’s not a single scene in the movie that was shot after 1994. Whether that’s an exaggeration or not, the sheer amount of archival material on display here (much of which has never been seen before) is remarkable and effectively brings that era in the studio’s history to vivid life.

Unfortunately, all too often the movie’s breadth comes at the expense of its depth. In his understandable desire to keep the narrative moving along, Hahn rushes through events and conflicts that cry out for more exploration. For example, far more time could have been spent examining the contentious relationship between Disney’s old guard and the new class of animators that started arriving in the early ‘80s and how that affected the films produced at that time, including the much-maligned Black Cauldron. The treatment of that movie in particular sets an unfortunate pattern that Hahn repeats throughout, namely using a film’s box-office gross to deem it a creative success or failure. (Granted, that’s an accurate reflection of how Hollywood judges its product, but it’s unfortunate to see a movie that’s in large part about the artistry of filmmaking fall into a similar trap. Then again, perhaps I’m just oversensitive because I really don’t think Black Cauldron entirely deserves its bad reputation.)

Similarly, it would have been fascinating to learn more about the studio’s original vision for Beauty and the Beast as well as Aladdin’s well-documented script changes (among the late-inning deletion of the title character’s mother) from the people involved with both movies first-hand. In fact, by the time Hahn gets around to Aladdin and The Lion King, he’s stopped dwelling the movies themselves and focuses the brunt of his attention on such real-world incidents as the famous Eisner vs. Katzenberg power struggle and Disney’s aggressive expansion into non-cinematic areas like international theme parks and TV networks. To be fair, this material is an important part of understanding the studio’s difficult evolution into the media colossus it is today so it wouldn’t have been right for Hahn to leave it out entirely.

And maybe that’s the root of my problem with Waking Sleeping Beauty: it’s a film that attempts to address both the art and commerce behind Disney’s comeback, but is constantly torn between those two competing impulses. Hahn certainly has enough material to make two separate films—one about the movies and one about the business—and I may have preferred that to the middle-of-the-road approach he takes here. In the end, the most obvious sign that Waking Sleeping Beauty is a Disney movie through and through is that it doubles as both an entertaining feature film and, more importantly, an effective commercial for the company’s merchandising arm. I know that when the credits rolled, I was already plotting a trip to Amazon to pick up the missing DVDs from my collection and maybe a stuffed Sebastian the Crab or two. You know…for my two-year-old.

Waking Sleeping Beauty is playing in limited release now.

No Responses to “ Animation Nation ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.