Wed 24 Mar 2010

A Tale of Two Nations

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

Comments Off on A Tale of Two Nations

Reviews of the new documentaries Kimjongilia and Ghost Town

Kimjongilia

Directed by N.C. Heikin

**

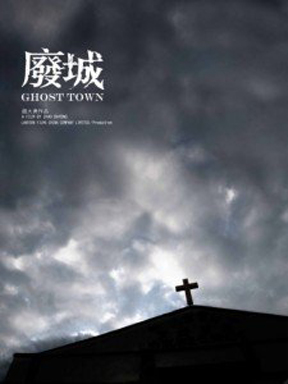

Ghost Town

Directed by Zhao Dayong

***

Among the books that made their way onto my summer reading list last year were two tomes about the 20th century histories of China and North Korea with a specific emphasis on the dictators that controlled those countries for decades–Mao Zedong and Kim Il Sung respectively. (For those interested, the two books were Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday and Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader by Bradley K. Martin, both of which I highly recommend.) That double-bill wasn’t planned entirely on purpose; growing up, I lived in Hong Kong for four years–leaving right before its 1997 handover from England to China–and had an interest in the region ever since. In fact, I had bought the Mao book years earlier fully intending to read it then, but kept putting it off.

On the other hand, it wasn’t until fairly recently that I started devouring information about North Korea, starting with, of all things, a comic book–specifically Guy Delisle’s fantastic travelogue Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea, which covered his trip to the nation’s capital in the late ’90s. Encouraged further by Yodok Stories, a moving documentary about survivors of North Korea’s gulags which I saw at last spring’s Tribeca Film Festival, I picked up Martin’s book to get an overview of how the country became the police state it is today. As it turned out, reading Mao and Fatherly Leader back-to-back made for a great pairing because the stories of how Mao and Kim Il Sung shaped China and North Korea in their own image–and, more significantly, what happened to each nation after the two men died–parallel each other nicely.

To say that both leaders were tyrants would be an understatement; most of the restrictive economic and social policies they launched proved disastrous and their sustained campaigns of fear and intimidation resulted in millions upon millions of deaths. Today, however, China bears little resemblance to the country that Mao ruled, while North Korea remains stagnant and suffering under the hand of Sung’s son, Kim Jong Il. The veil of secrecy that shrouds the country is what makes it such a compelling place to study. Simply put, it’s difficult to imagine how a totalitarian society like North Korea can still exist in the 21st century and the desire to learn what life there is like–particularly because video footage and photographs of life outside the capitol rarely make it across the border–fuels many of the books, films and websites that have cropped up in the past few years.

The newest entry in this growing syllabus is N.C. Heikin’s documentary Kimjongilia, a 70-minute overview of the current state of things in North Korea that’s made up largely of emotional interviews with defectors interspersed with footage from propaganda films as well as the nation’s famously lavish parades that celebrate Kim Jong Il and Kim Il Sung. If this is your first exposure to the subject, the movie provides a decent introduction to the many ills that plague North Korean society, not the least of which include widespread hunger, forced imprisonment in hellish labor camps and a rigid class system that protects the Dear Leader and his sycophants while forcing common citizens to fend for themselves. If, on the other hand, you’re already familiar with much of this material, Kimjongilia has little else to offer. In fact, it’s a distractingly superficial depiction of North Korea, one that boils down the country’s complex history to a handful of bullet points and struggles to make any coherent arguments beyond the obvious–i.e. “North Korea is hell and Kim Jong Il is a monster.”

In the far superior Yodok Stories, director Andrzej Fidyk wisely chose to center the movie around a North Korean theater director who had escaped to South Korea and his efforts to stage a dance performance depicting life across the border that incorporated the testimony of other defectors. That narrative spine allowed Fidyk to branch off and pursue the individual stories of the men and women interviewed in the film without losing a basic sense of structure. Kimjongilia is far less disciplined; there seems to be little rhyme or reason to how Heikin has chosen to assemble the interviews or the assorted B-roll material she’s gathered. (I also noticed that Heikin recycles specific archival shots on more than one occasion and not because she’s trying to make a specific point–it just appears that she didn’t very have much footage to work with.) A former dance student, Heikin also filmed a lone dancer going through various routines and sprinkles that footage throughout the movie. No doubt intended as a way to enhance the emotion of her subject’s stories, these dance interludes instead seem more like filler, a way to pad out this too-slender documentary to feature length.

“Superficial” is one word that can’t be used to describe Zhao Dayong’s Ghost Town, a three-hour documentary that chronicles the slow, steady death of a remote mountain village in contemporary China. (The town’s name is never given in the film, but the production notes reveal that it’s the village of Zhiziluo, located nearby the China-Myanmar border.) Working in the tradition of groundbreaking documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman, Dayong films long, unbroken takes that give the audience plenty of time to soak in the details of this crumbling town and its world-weary inhabitants. (Or, in some cases, struggle to stay awake. Ghost Town is fascinating, but I’d be lying if I said that there weren’t times that I had to fight to keep my attention focused on the screen.) Also like Wiseman, he also doesn’t go out of his way to impose a narrative on the movie. While Ghost Town does tell a story–in fact, it tells three–the “plot” emerges from the ordinary details of daily life in Zhiziluo rather than any external conflict.

Dayong’s primary concession to conventional narrative structure is to divide the movie into three distinct sections, each one focusing on a specific set of the village’s residents. Part 1, entitled “Voices,” follows Zhiziluo’s local Catholic pastor and his elderly father, who converted to the faith decades ago when missionaries passed through town. Meanwhile, the second part, “Recollections” tackles the subject of love and marriage, introducing us to a recently divorced man whose wife has moved to another town along with their two sons and a young couple that would like to be married but are being driven apart by financial concerns. The final installment, “Innocence,” is a profile of a 12-year-old orphan named Ah Long, who has had to survive on his own since his parents abandoned him as a young child. Of these three chapters, “Innocence” is the most gripping, largely because Ah Long is such a compelling personality. Initially coming across as a streetwise tough, he eventually reveals a vulnerability that’s quite touching. But the other two sections have their moments as well; “Recollections” concludes with a powerful scene of a married woman describing the difficult choices facing her in stark terms and “Voices” provides an intriguing glimpse at the small, but reverent Christian community in this part of China, who come from miles around to attend the pastor’s Christmas mass.

Many recent documentaries about China have chosen to focus on how the country’s ongoing rush to modernity, which began in the wake of Mao’s death and kicked into overdrive in the ’90s quickly transforming the nation into the economic powerhouse it is today, has created a great divide between those who have moved to inhabit gleaming metropolises and the people that have remained behind in rural outposts like Zhiziluo. Films like Up the Yangtze and Last Train Home make a persuasive case that the demands of big-city life in present-day China have negatively affected citizens’ connections with their families and their own agrarian histories. Whether intentionally or not, Ghost Town posits the exact opposite argument. Far from holding up Zhiziluo as some sort of standard other communities should aspire to, the film shows that towns like this one have nothing left to offer its residents. With no work available and no money from the local or central government to rebuild its crumbling buildings, it will continue to fall to pieces while young people continue to move away in pursuit of paying jobs that can at least give them the hope of a better life. In the end, all that will be left will be a statue commemorating another ghost–the long-dead Chairman Mao–presiding over the ruins of a ghost town.

Kimjongilia is currently playing in limited release in New York. Ghost Town recently concluded a week-long run at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and will be playing at individual screenings in Wisconsin, New Mexico, Colorado and California in April. Visit the movie’s official websites, Kimjongiliathemovie.com and dgeneratefilms.com for more information.

No Responses to “ A Tale of Two Nations ”

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.